Why is Web Performance Undervalued?

Web performance is one of those things so fundamental to businesses that you would expect them

to absolutely nail it. If consumers care about performance, which seems to be true, then in an efficient, competitive market you

would expect businesses to be under immense pressure to optimize it. And yet, poor web

performance is ubiquitous. Huge companies across the board are shipping websites and web apps so sluggish that it is killing the web.

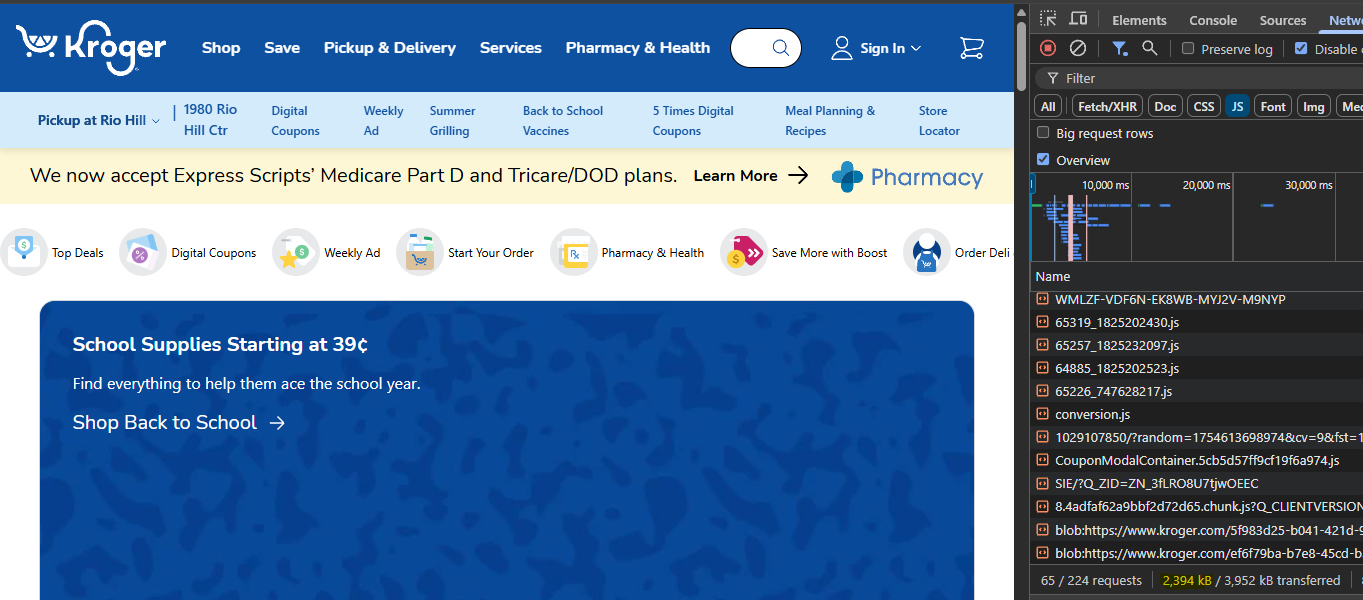

The economic upside of getting it right isn't tiny either. Years ago while working at Kroger,

Taylor Hunt calculated that each KB of JavaScript sent to the client was costing the company $100,000 per year, as a lower bound. How much is Kroger sending today?  Oh, Just 2.4 Megabytes. Out of a chonky 4 MB payload. Assuming they could rebuild the

site to hit Alex Russell's target of 450 KB, that's

conservatively $195,000,000 per year. Not too bad. And this is likely a profound underestimation of the real gain. As Taylor mentions

in a podcast, dramatic gains in performance

wouldn't just lead to predictable linear gains in revenue. They would inspire unpredictably

large changes in user behavior as users realized the newfound feasability and convenience. Why

on earth would any company leave that on the table?

Oh, Just 2.4 Megabytes. Out of a chonky 4 MB payload. Assuming they could rebuild the

site to hit Alex Russell's target of 450 KB, that's

conservatively $195,000,000 per year. Not too bad. And this is likely a profound underestimation of the real gain. As Taylor mentions

in a podcast, dramatic gains in performance

wouldn't just lead to predictable linear gains in revenue. They would inspire unpredictably

large changes in user behavior as users realized the newfound feasability and convenience. Why

on earth would any company leave that on the table?

Maybe companies just don't care?

This doesn't seem to be the case. There is a strong demand for faster websites in the market. Performance consultant Harry Roberts is keeping busy. Alex Russell's job of supporting product teams has been totally engulfed by remediating performance issues. The reaction of management to Taylor's Kroger-lite version of the website "exceeded even [his] most indulgent expectations". Of course it did! In the Kroger-lite demo adding eggs to the cart and getting to the checkout screen took 20 seconds. The live version took 3 minutes and 44 seconds. No one can use those services side by side without admitting the drastic difference in user experience.

People and businesses want their websites to be faster. Tammy Everts has been researching this for over a decade, and she's thankfully verified the common sense that people find slow websites extremely frustating. What's crazy is that we hate slow websites so much that a slow experience sours everything. People will think that a slow website has a poorer design as a whole. They'll find it more confusing, more tacky, even more boring. Slow websites are a mismatch between our technology and our evolved expectations of reality. We evolved in a world of instantaneous feedback: building shelter, gathering food, hunting, face to face conversations, etc. None of these things lag, and even the things which weren't instantaneous to complete, like chopping down a tree, at least gave instantaneous signs of progress. This is why we prefer to see spinners or progress bars during long tasks; It's at least some feedback that our actions had an effect. Slow websites suck. I know it. You know it. Science knows it. Business leaders know it. Why don't they invest in it?

Maybe feature development sucks up all investment?

This is certainly a large factor. In my own professional life as a software developer the vast majority of my time goes to developing new features. The business is laser-focused on offering new capabilities that our clients ask for. What if the clients never ask for better peformance? For B2B software this is likely true. B2B software is bought based on what excecutives saw on LinkedIn recently. Big contracts are made, the software becomes deeply integrated, and switching costs become incredibly high. Had the buyer been forced to heavily use the product in some trial period, cases like this would be avoided. Alas... it's a classic principal-agent problem. I genuinely believe B2B software will never have good performance for this reason. Features on the other had are vital to sales of this software. Sales pitches are effectively feature enumeration. Marketing sites are stuffed full of things the software can do, not proof that it does those things well. Bonus points are awarded for having the feature du jour. You can say that your product is fast, but everyone says that. Without widely-shared metrics the claim of speed is based on the seller's word alone; It's a market for lemons. When every lemon of a site can claim to be "fast", the buyer is helpless at distinguishing the good from the bad. Core Web Vitals at least have the potential to disrupt this.

What about B2C?

All of the examples in my first paragraph are B2C websites/apps. If consumers deeply value performance, how can it be that these sites are slow? It's important to distinguish sites with high switching costs. Music producer Rick Beato mainly uses spotify, despite his personal distaste for its effect on his industry, because he's got a huge backlog of playlists saved on it. People are slow to leave Facebook or Twitter due to the network effects; It's tough to move when everyone you know is still on the old platform. These kinds of sites and apps are prime for enshittification. When customers can't easily switch, sites are free to degrade without a hit to their bottom-line. And if Mr.Doctorow is to be believed, businesses which can degrade will degrade(at least big ones).

Ok so B2B and large, entrenched B2C can effectively ignore performance. Just ignoring those cases already filters out a huge portion of the market, so the undervaluing is starting to make sense. But what about the rest? Genuine, competitive products for the consumer on the free marketplace. Who would ever use Kroger.com to buy eggs? I think this is the section of the market that saddens Alex Russell so much. This is the place where the web should be winning, but instead it's slowly dying. What happened to Kroger is symptomatic of the entire front-end industry. Kroger's performance potential was killed by React. Well, that's a little dramatic. It's more that the React architecture was unable to be optimized much, and any optimizations that happened were clobbered by other teams adding new features. The problem with the industry isn't just React, but React is THE ubiquitous technology in the space right now. The real problem is ultimately another principal-agent problem: tools were selected for developer experience, not user experience.

Developer Experience > All

Look at this quote from the React Conf 2015 Keynote:

So people started playing around with this internally, and everyone had the same reaction. They were like, “Okay, A.) I have no idea how this is going to be performant enough, but B.) it’s so fun to work with.” Right? Everybody was like, “This is so cool, I don’t really care if it’s too slow — somebody will make it faster.”

Right from the start, React was chosen because developers like coding with it. I'm damn suspicious that what people really liked was JSX, which was a genuinely cool innovation. But thanks to React's rendering strategy it was never a good choice for performance1. Didn't matter though, because most teams didn't have guardrails in place to prevent performance regressions. Managers certainly didn't understand the tradeoffs between various JavaScript libraries, so that choice was deferred to the developers. With no obvious constraints on that choice they picked the techologies that made their lives easier, at least in the short term(*ahem* LLM-coding). It's easy to blame managers for letting their projects run amok, but it feels to me like this degradation was inevitable. Most manangers understand very little about the web, and with websites being so fast for so long I'm not surprised that web performance wasn't even a thing they thought to worry about. And even fewer would know that slow sites meaningfully harm revenues2.

React and other SPA frameworks abstracted web fundamentals enough to make new developers quickly productive. With the market's insatiable hunger for web development in the 2010's thousands of new front-end devs were minted and given the keys to the castle. Perhaps a slower growth curve would have allowed for more mentorship in prudent engineering, and this all might have been avoided, who knows? But in this environment SPAs came to dominate, and eventually it was nearly all React. Add in bloated dependency trees from npm and you get the outrageous payloads we saw earlier.

Can the web recover?

Personally, I'm optimistic here. Core Web Vitals and other standard performance metrics are becoming more well known. The front-end community is slowly falling out of love with React, and even out of love with SPAs in general. Static site generators like Astro and Eleventy are getting a lot of attention because they're simple and good enough for what most people need. Those sticking with SPAs can have much better performance by using signals. I think the long, painful road of neglecting performance will eventually come to an end. And thankfully the business case for good performance is so strong that getting management buy-in shouldn't be too hard. But I can't ignore the end of Ryan Hunt's story at Kroger. That organization had a wildly better site in hand, but it couldn't overhaul it's own sprawling React culture enough to adopt the lite app. The immense investment teams have put into learning, building, and tooling their current sites are undoubtedly the main impediment to better performance. It's hard to justify the pain needed to leave it all behind. In the end though I think market forces will figure this out. It might not happen very quickly, but the upside to getting it right is just so powerful. In the meantime, I think the best thing to do as a developer is learn web and performance fundamentals. They say all value eventually regresses to the fundamentals. Maybe then your skills will be fully valued too.